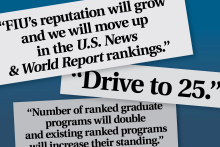

Florida International University appears as a top-50 university on three lists. By 2025, it wants be on 10.

On the University of Houston’s strategic-plan website, it lists a prominent “milestone”: that Houston “will rank among the top 75 and then among the top 50 public universities in the nation in the U.S. News & World Report ranking.”

Washington State University calls its goal to be one of the nation’s top public research universities the “Drive to 25.”

Over the last two decades, the U.S. News “Best Colleges” rankings have sustained intense criticism for rewarding wealthier institutions, for weighting “inputs” over “outputs,” and for being poor indicators of colleges’ quality. Yet public colleges are still using the rankings and those they inspired to measure their own success.

The magazine’s annual ranking of national universities was released Monday. To mark the occasion, The Chronicle searched the current strategic plans of the country’s 100-largest public four-year universities for mentions of the all-important list and others like it. About a quarter of the plans explicitly affirm the importance of rising in national rankings. Many of these documents check U.S. News by name.

This prevalence — while unlikely to surprise those who work in higher ed — is a striking testament to public higher education’s continued pursuit of an accolade that many have said is antithetical to the mission of state-funded education.

In current strategic plans, several colleges state their rankings goals outright. At Clemson University, for example, a strategic plan endorsed by the university’s Board of Trustees in 2016 starts out with a simple vision statement: “Clemson University will be one of the nation’s top 20 public universities.”

To employ the “philosophy of continuous improvement,” the university identified the U.S. News rankings as one of the main metrics against which it will measure itself. (Clemson has a history of emphasizing the rankings; in 2009, The Chronicle reported that the university had an almost single-minded focus on them.)

There are now so many U.S. News sublists to choose from, too, that some colleges have more granular goals for specific departments. At Oklahoma State University at Stillwater, the College of Engineering, Architecture, and Technology has a strategic plan with clear, rankings-based goals for each of its programs. Engineering will rise into the top 40, architecture to 25, and engineering technology will reach the top 10.

The actions Clemson names as a means of improving its overall ranking are hard to argue with. The university will “increase six-year graduation rates to 85 percent,” “increase freshman-to-sophomore retention rates to 96 percent,” and ”increase doctoral degrees awarded annually by 50 percent to 330.”

Rising in those metrics certainly would help a college’s score. Graduation rates and retention account for 22 percent of U.S. News’s calculation. But F. King Alexander, the former president of Louisiana State and Oregon State Universities and an avid critic of the rankings, says those metrics privilege schools with wealthier students.

“Everybody knows how to get graduation and retention rates up,” he said. “You turn down every academically challenged student.” Wealthy students, he added, tend to graduate. (Alexander resigned as president of Oregon State after his handling of a sexual-misconduct scandal at LSU drew scrutiny.)

Robert H. Jones, Clemson’s provost, said in an interview that the university is not chasing any particular rankings system, even though it does mention U.S. News in its plan. But administrators maintain that some elements of the ranking are worth pursuing, such as student graduation rates and the scholarly reputation of the faculty.

“So we’re putting all our chips into driving those up. If you do that,” he said, “you’ll be treated well by the ranking systems out there.”

But Jones added that in a new strategic plan Clemson is drafting, the university is moving away from an emphasis on rankings.

Some plans acknowledge the troubling downstream effects of U.S. News’s supremacy, and promise they won’t blindly chase the prestige that rankings promise. “Setting goals that strategically align with improving national rankings to increase visibility and enhance institutional reputation can inadvertently negatively affect demographic diversity and limit student access,” Florida International University’s strategic plan reads. “FIU rejects this paradigm.”

A few colleges seemed to express a tortured relationship with the annual academic beauty contest. Midway through the strategic plan of the University of Minnesota—Twin Cities, the authors spend a paragraph discussing the philosophy of rankings. “We intentionally do not express our desire to transform the university as a quest to improve our rankings,” the report reads. “Targeting a particular place in the rankings does little to affect institutional culture.”

Yet, the report asserts, “we live in a rankings-conscious world” and “rankings (including those of public research universities) cannot be ignored.” And so, the report promises: “A high ranking is likely to be the outcome or byproduct of a high-functioning university.”

Washington State, with its “Drive to 25,” acknowledges that “rankings in themselves may imply a danger that we are seeking to become elite, thus jeopardizing our focus on people.” The university’s plan says it doesn’t want to become more exclusionary, just better at what it does.

The pattern among some public colleges of privileging rankings in their plans is especially striking because previous analyses have found that the rankings exacerbate inequality. A 2017 analysis by Politico showed that the rankings created incentives for universities to favor wealthy students.

In the last few years, U.S. News has tried to confront those criticisms. In the 2020 edition of “Best Colleges,” published in September 2019, editors added to their formula rewards for institutions that enroll a large share of Pell Grant recipients and graduate them at rates on a par with non-Pell students. In the 2021 edition, editors added graduates’ debt to the algorithm. Most of the strategic plans that The Chronicle read predate these changes.

U.S. News says its rankings are designed to give students and their families clear, helpful information that they can use to decide where to go to college.

That’s not what it does, according to Alexander.

“It’s designed for the wealthy and wealthy schools, and that’s always been what it’s about,” he said. “It’s been a quiet protection of the privileged class.”