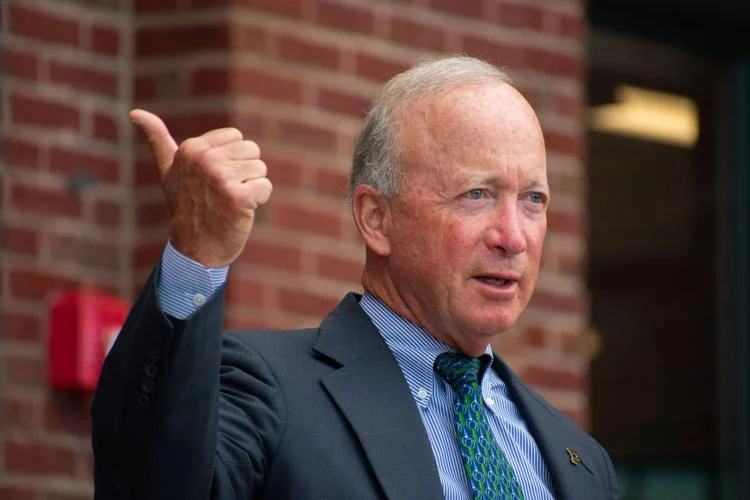

Purdue President Mitch Daniels wrote a column for the Washington Post in 2018 titled, “Government transparency has gone too far.” In it, while he agreed that many open-door laws have benefited society, he claimed society may have gone overboard regarding what should be considered public knowledge.

“Under ‘open meeting’ requirements forbidding members of governing bodies to confer privately,” he wrote, “the result is furtive hallway conversations or ‘executive committee’ meetings where the discussion might not technically fall into the category of exemptions that permit such meetings.”

That is what the president has apparently been doing with Purdue’s board of trustees.

Board packets and ‘advisory and deliberative’ information

Trustees meetings, which are typically held once a month, proceed in the same fashion each time. Items are brought to the board’s attention, board members look through allegedly confidential packets full of “advisory and deliberative” information, they will briefly discuss the details they wish to highlight and then they’ll quickly vote before they move to the next topic.

We requested the board packets for the June 11 meeting on June 5, and we were told by the board’s corporate secretary the items would be sent “after they have been approved.”

They were never sent.

Purdue spokesperson Tim Doty said in an email Friday that the board members receive board packets that contain information on the meeting agendas “well in advance,” giving board members time to study the material and understand issues. So why can’t we see them yet?

“There’s no reason you can’t be getting a copy at the same time as the trustees,” Steve Key said in a phone call Thursday.

Key, the executive director of the Hoosier State Press Association, argued that the board must provide the public with all of the decision-making information it has.

“Only rationale for withholding the board packet is the administration wants to control its message,” he wrote in a June email. “That isn’t a statutory basis for denying access to the records. In fact, it’s the antithesis of the statute’s intent.”

Board meetings typically leave no room for public comment. Members vote without much discussion, as if they have already come to a decision beforehand. An email from Doty in June seems to confirm that suspicion: “As soon as items are voted on or the meeting ends, we send out the news releases,” he wrote in answer to our question about a vague agenda item.

“That would indicate a decision was already made,” Key agreed.

During that particular meeting, news releases were sent out at about the same time as items were voted on – not even after the meeting ended. But if news releases were already prepared before the meeting, when were those decisions made?

Executive sessions

The board usually holds an executive session 24 hours before each public meeting. The purpose of an executive session is to discuss confidential matters and should be used “sparingly,” according to state law.

“They should not be held regularly, nor should they be a standing meeting on a governing body’s schedule,” the public access laws handbook reads.

State law defines specific instances in which an executive session out of public view is justified. To hold an executive session, a government agency must cite the specific state statute that pertains to each item to be discussed in secret.

“They have to let you know what items they’re gonna discuss behind closed doors,” Key said.

But the board seems to have found a creative way around this.

The trustees cite the same seven statutory exemptions listed in each notice of executive session (not counting “special meetings”) since at least June 2020, which is as far back as the board’s website goes. Sometimes, the number of statutes listed is actually higher than the number of items on the meeting agenda itself. How could it be that the board is always discussing items pertaining to the same seven exemptions each month?

What seems more likely to us is that the board is discussing every item on the agenda in an executive session or other private conversations, coming to an agreement behind closed doors and simply finalizing its vote in front of the public.

Daniels wrote in his Washington Post column that government has been “rendered less nimble, less talented and less effective,” by an increased transparency. But why would more transparency make them less effective? Isn’t that contrary to the spirit of open door laws for a public university supported by tax dollars?

In other words, the board is acting in the spirit of the philosophy Daniels espoused in his column.

Emails

If the board isn’t discussing these items in its executive sessions, it’s most likely doing so via email or phone call.

“Government took a serious wrong turn at the dawn of the email era when somebody decided that these online exchanges are ‘documents,’” Daniels wrote. “I’m rarely on a conference call with other public university presidents that doesn’t include someone reminding the group: ‘No emails!’”

The board making decisions via email is technically not a violation of the law, since copies of emails and phone recordings do fall under the purview of public records and can hypothetically be requested by the public. But by adding levels of secrecy and hoops for information-seeking citizens to jump through, it goes against the spirit of what open door laws are supposed to do: Allow the public to monitor officials and hold them accountable.

The Exponent requested emails sent between board members, and from them to Daniels, regarding the discussion surrounding a controversial decision on requiring civics literacy made in June, but hasn’t yet received any documents. The decision was controversial because of the large number of faculty members who were strictly against it, and the board made its decision against the vote of the University Senate. In fact, faculty from Purdue’s satellite campuses were unaware the decision affected them until a week before the meeting.

Open discussion of the topic was limited in the meeting, and the questions posed seemed to highlight only positive aspects of the proposals, as if the questions were scripted.

What were the real concerns trustees had? Who did they consult? Did anyone vote against the measure, in line with the faculty’s objections? We don’t know any of that, because the process was apparently out of the public view.

We need more transparency

Perhaps Daniels and the trustees don’t realize what Indiana’s open door laws say, or the image of secrecy they are projecting.

In our Thursday edition, we included a note about this editorial and the board’s tendency toward secrecy. After noon, we discovered more information from the last two meetings had just been released on the board of trustees website. That information provided more detail on some, but not all, of the items discussed in the two meetings.

It’s important to note that only those with a Purdue email can access this part of the website.

The board of trustees has repeatedly acted against the spirit of public access laws. We call on the board to be more transparent. Discuss, deliberate and debate in public. Make decisions in public. Finalize votes in public.

And please, give the public access to the same information that’s apparently so readily available to you.

The Editorial Board is composed of The Exponent’s summer staff and written by its editor.