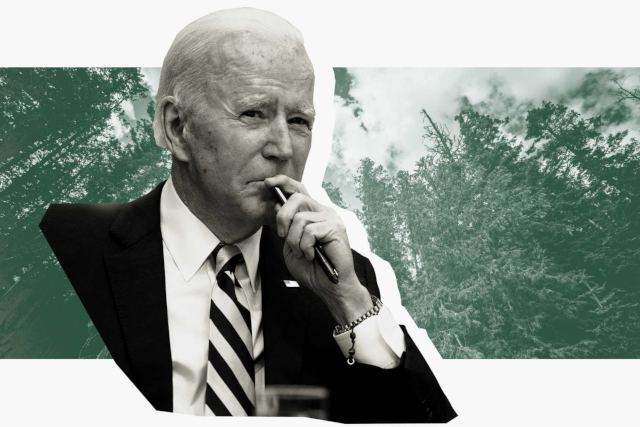

The Biden administration is a single regulatory leap away from green-lighting the logging of hundreds of acres of old-growth forest in Montana. If approved, the U.S. Forest Service’s “Black Ram Project” would authorize commercial harvesting on 3,904 acres in the Kootenai National Forest, including the clear-cutting of at least 579 acres of trees that are hundreds of years old. On top of potentially violating the National Environmental Policy Act, carrying out the Trump-era project would undermine at least three major Biden administration commitments: tackling the climate crisis, preserving 30 percent of federal land and waters by 2030 and preventing future outbreaks of disease transmitted from animals (or zoonoses) like COVID-19.

The Kootenai National Forest is in the northwestern corner of the state. Swaths of its land are still covered in 600- to 800-year-old subalpine fir, western larch and spruce trees, which ascend from the headwaters of the Yaak River. The ecosystem serves as a vital corridor for species such as wolves, lynx, wolverine, mountain goats and grizzly bears.

“Reefs of clouds drape themselves over its peak, and artesian seeps and springs percolate out of the steep east-facing mountain wall, home to sensitive and threatened plants,” local activist Rick Bass wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2002, describing the Yaak Valley specifically. “Wild ducks nest in the hanging marshes, salamanders wriggle beneath rotting logs and the area is favored by one of only two breeding female grizzly bears known to be left on the entire two-million-acre Kootenai National Forest.”

According to the Forest Service’s environmental assessment, the Black Ram Project was first publicly proposed in 2017, and is intended to “maintain or improve [the forest’s] resilience to disturbances such as drought, insect and disease outbreaks, and wildfires.” But the project doesn’t reduce the potential for high-intensity fires, Aaron Peterson, executive director of the conservation group Yaak Valley Forest Council, told Truthout.

Logging-as-fire-prevention grew popular during the Trump administration. In August 2019, for example, Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-California) and Sen. Steve Daines (R-Montana) introduced bipartisan logging legislation proposed to speed up the permitting process for cutting down trees in national forests “to protect communities from wildfires.” In contrast with the Indigenous practice of controlled burns, logging can actually make things worse. According to a 2016 study in Ecosphere, in forests where trees have been removed by logging, fires burn hotter and faster since the presence of fewer trees can promote the spread of invasive and highly combustible grasses, thus creating hotter, drier and windier conditions.

“We’re of the mind that we should be cutting more small-diameter trees closer to settlements of humans, not miles and miles and miles into the backcountry,” Peterson said. “These old 600- to 800-year-old trees are doing their job.”

Forests pull an estimated one-quarter of all human-generated carbon dioxide emissions from the atmosphere each year. And the larger the tree, the more carbon it can store. A study on six national forests in Oregon suggests trees with trunks 21 inches in diameter or greater make up 3 percent of those forests, but store 42 percent of above-ground carbon. While tree-planting initiatives have become a popular action among environmental groups, “protecting and restoring existing forests rarely attracts the same level of support,” Beverly Law, professor emeritus at Oregon State University, co-wrote in The Conversation.

In comments to the Forest Service submitted in August 2019, the Kootenai Tribe of Iowa — one of the Indigenous groups that in 1855 was granted fishing, hunting and gathering rights within what is now the Kootenai National Forest, but is not currently able to exercise it — noted its support for some elements of the Black Ram Project. But it also pointed out that the Forest Service was overly vague about the project’s potentially negative impacts, such as the possible snowball effect of opening new roads in old growth areas. The tribe’s fish and wildlife director Sue Ireland did not respond to Truthout’s request for comment ahead of press time.

In January, the Forest Service responded to 69 issues raised in public comment objecting to the project, and in doing so, effectively dismissed those comments, said Ted Zukoski, an attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity. Their responses signal that the project will advance following the issuance of a final biological opinion from U.S. Fish and Wildlife on the project’s likely impact, or lack thereof, on endangered grizzlies.

Zukoski said that the project is at odds with two of President Biden’s executive orders: EO 13990 protecting public health and the environment, and EO 14008 tackling the climate crisis at home and abroad. “The science is clear that safeguarding old forests and allowing forests to grow older — as compared with logging and planting tree seedlings — provide significant natural carbon storage benefits,” Zukoski told Truthout.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which houses the Forest Service, has a long history of managing trees as commodity crops and promoting clear-cutting and other practices that maximize yield and profit, as Oregon Public Radio’s Aaron Scott has reported on extensively. By the mid-1980s, timber was the highest-valued crop in the U.S. and the Forest Service was tasked with selling it, Scott has reported.

The land that is now known as the Kootenai National Forest has been long impacted by that approach. In 2006, an anonymous female member of the confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes responded to a survey for a dissertation on tribal forest management by Victoria Lynn Yazzie. “The woods are no longer an interest to me,” the anonymous tribal member wrote. “Its sights are devastating. The clear cuts have [left] nothing but thistle, weeds and [it’s] not pleasant to see how machinery tore up vast areas … I don’t enjoy seeing this.”

But conservation groups, working in collaboration with tribes in some cases, have managed to restore and preserve many of these ecosystems, such that the Kootenai region is still what climate activist Bill McKibben describes as “one of the wildest places remaining in the lower forty-eight states.” There are now an estimated 24 grizzly bears in the Yaak Valley, including four or five females, up from the two Bass reported in 2002, though one was brutally killed in November 2020, her paws skinned and partially mutilated, dumped in a driveway.

Heartbreaking in its own right, that’s an additional reason the Black Ram Project undercuts Biden’s public health efforts. In two major reports released in 2020 — one by the World Wildlife Fund and the other by members of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) — researchers warned that 631,000 to 827,000 unknown viruses in nature could still infect people, and that stopping deforestation and minimizing opportunities for the transfer of pathogens between wild animals and people is key to preventing the next major outbreak of disease.

“The same human activities that drive climate change and biodiversity loss also drive pandemic risk,” Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance said in a statement accompanying the IPBES report. “Changes in the way we use land; the expansion and intensification of agriculture; and unsustainable trade … disrupt nature and increase contact between wildlife, livestock, pathogens and people. This is the path to pandemics.”

To proceed with the Black Ram Project as proposed would require a blatant neglect of those recommendations. In Alaska, zoonotic infections linked to grizzly bear-human interactions include brucellosis and trichinellosis. According to a February 2020 literature review of 90 years of research in the journal Zoonoses and Public Health, other zoonotic diseases linked to grizzly bears include tularaemia — a bacterial disease that can lead to skin ulcers and be fatal — and tapeworm. In spite of shrinking populations, the authors found, many bears continue to be hunted and humans often consume their meat. “The legal and illegal trade of bears and bear products, such as bile harvested from gall bladders … bring humans into close contact with zoonotic pathogens that may be circulating in bear species.”

Peterson says he’s not sure about the zoonotic risks of disease from bears in the Yaak Valley. What he does know from experience is that “an open road is an invitation to human-bear conflict,” which could include more violent incidents of poaching like what happened in November.

According to a representative from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there is no set completion date associated with the final biological opinion. Now that Tom Vilsack has been confirmed as head of the USDA, Zukoski says he remains hopeful the agency might embrace climate and ecological science by blocking the timber sale in the Yaak Valley, which Vilsack has the full authority to do. “Secretary Vilsack’s review of the Black Ram logging project will be a major test of whether the secretary will follow the president’s climate and conservation direction, or will continue liquidating old forest following the Trump blueprint,” he said.

But Vilsack’s record on logging doesn’t inspire total confidence. As secretary of agriculture during the Obama administration, Vilsack signed a directive granting himself sole power to make decisions on harvesting timber in roadless areas, and shortly thereafter allowed the clear-cutting of 381 acres of rainforest in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest. “It is the judgment of the U.S. Forest Service that the sale is critical to keep a local timber mill open and to protect jobs associated with that mill,” a USDA spokesperson told E&E News in 2009.

This time around, Vilsack’s USDA might consider creating jobs by establishing a federal forest carbon reserve system that protects remaining mature and old forests across the national forest system, including old growth in the Yaak Valley — which, as Peterson reminds us, is currently classified as inland rainforest.

“If hundreds of acres can be clear cut, it will look like Siberia,” Peterson said.