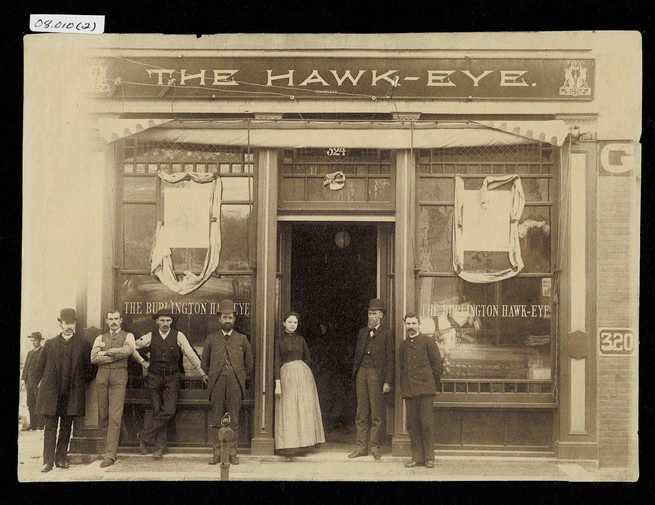

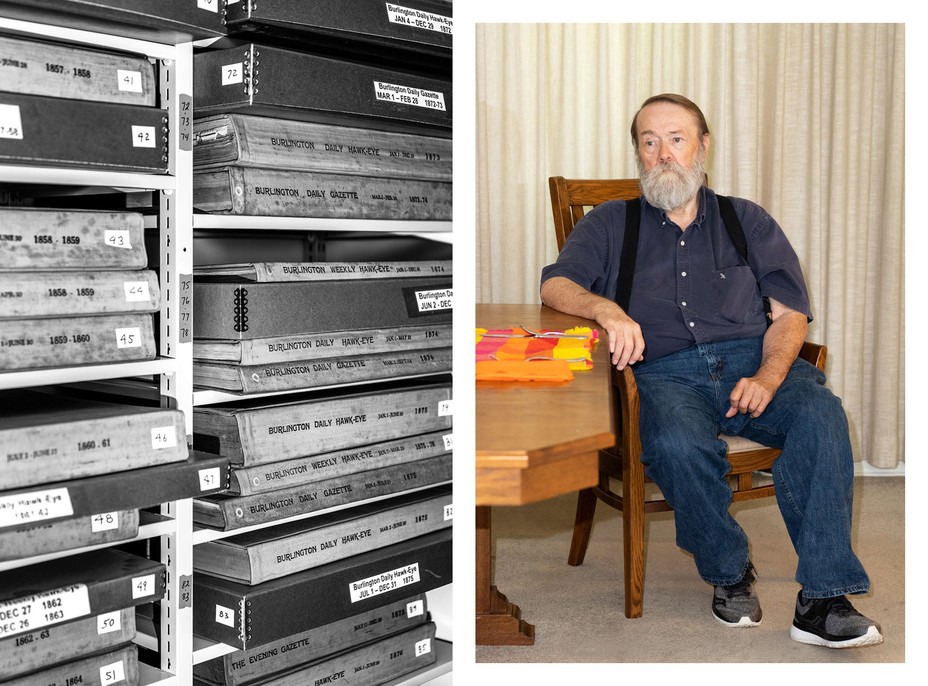

We don’t often talk about how a paper’s collapse makes people feel: less connected, more alone. Dale Alison saw the blast up close. He was 32 years old, and it was his first day as the city editor of The Hawk Eye, a newspaper in Burlington, Iowa. From the front door of the office, he saw the train tracks outside ripple, and the air seemed to vibrate and sway. Then the windows of the newsroom blew out. Alison and his colleagues ducked under their desks, and a few looked out to see a plume of black smoke blocking the sky. The 12-story grain-storage facility—a longtime fixture on Burlington’s riverfront—was wrapped in orange flames. Alison started shouting out assignments. Matt Gallo should head to the hospital; Susan Fisher and Mike Sweet should drive downtown for man-on-the-street interviews; Steve Delaney, Tony Miller, and the photographers should go straight to the scene. Within the hour, firefighters evacuated the newsroom (train cars containing anhydrous ammonia were parked perilously close) and everyone regrouped at a nearby dive bar. Reporters made calls from the payphone and scrawled their stories on reams of paper someone had nabbed from an old typewriter shop. Photographers developed their film in a bathtub at someone’s house on the northwest side of town. By late afternoon, the newsroom had reopened, and the presses were rolling. Burlingtonians had their papers by 8 p.m., just three hours behind schedule, complete with a full-size photo of the fireball and aerial images from the scene. The blast had injured some workers, but miraculously no one died. It had shattered hundreds of windows downtown and sank a nearby barge. Even now, veteran Hawk Eye staffers will tell you that the grain-elevator explosion was a career highlight. It gave them the kind of thrill that all reporters crave. But there was also a real sense of ownership to the story: This was Burlington’s disaster—an event with an immediate impact. There was no question that The Hawk Eye would cover it from every possible angle. Throughout the next year, the newspaper published a series of follow-up stories, including investigations into the explosion’s cause (a bearing had overheated and ignited a buildup of grain dust) and the company’s safety standards. The blast had been just the latest in a string of elevator fires in the Midwest, and the paper’s business editor, Steve Delaney, chased the story for months. By the end of the year, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration had announced new safety requirements for grain elevators. For the people of southeastern Iowa, knowing that The Hawk Eye was investigating this fiasco was a source of comfort. The paper’s reliable attention made us feel like our little part of Iowa mattered and that we did, too. This is what The Hawk Eye gave us. Back then, we took it for granted. I grew up outside Burlington, 15 miles west on Highway 34, past alternating corn and soybean fields and past the 19,000-acre Iowa Army Ammunition Plant. But Burlington was my community—home to the nearest supermarket, the mall, the movie theater—and The Hawk Eye was how we kept up: It’s where I looked for summer jobs, how my mother and I tracked down weekend tag sales, how we heard which new stores and restaurants were coming to town. The paper was where we first learned that my close friend’s father had died in a Mississippi water-skiing accident. It was where my high-school Girl Scout troop got a half-page spread our senior year. The Hawk Eye isn’t dead yet, which sets it apart from many other local newspapers in America. Its staff, now down to three overstretched news reporters, still produces a print edition six days a week. But the paper is dying. Its pages are smaller than they used to be, and there are fewer of them. Even so, wide margins and large fonts are used to fill space. The paper is laid out by a remote design team and printed 100 miles away in Peoria, Illinois; if a reader doesn’t get her paper in the morning, she is instructed to dial a number that will connect her to a call center in the Philippines. Obituaries used to be free; now, when your uncle dies, you have to pay to publish a write-up. These days, most of The Hawk Eye’s articles are ripped from other Gannett-owned Iowa publications, such as The Des Moines Register and the Ames Tribune, written for a readership three hours away. The Opinion section, once an arena for local columnists and letter writers to spar over the merits and morals of riverboat gambling and railroad jobs moving to Topeka, is dominated by syndicated national columnists. By now, we know what happens when a community loses its newspaper. People tend to participate less often in municipal elections, and those elections are less competitive. Corruption goes unchecked, and costs sometimes go up for town governments. Disinformation becomes the norm, as people start to get their facts mainly from social media. But the decline of The Hawk Eye has also revealed a quieter, less quantifiable change. When people lament the decline of small newspapers, they tend to emphasize the most important stories that will go uncovered: political corruption, school-board scandals, zoning-board hearings, police misconduct. They are right to worry about that. But often overlooked are the more quotidian stories, the ones that disappear first when a paper loses resources: stories about the annual Teddy Bear Picnic at Crapo Park, the town-hall meeting about the new swimming-pool design, and the tractor games during the Denmark Heritage Days. These stories are the connective tissue of a community; they introduce people to their neighbors, and they encourage readers to listen to and empathize with one another. When that tissue disintegrates, something vital rots away. We don’t often stop to ponder the way that a newspaper’s collapse makes people feel: less connected, more alone. As local news crumbles, so does our tether to one another. As a teenager, I read the newspaper occasionally, but not like my dad, who practically absorbed it every morning with his coffee and Raisin Bran. One of my earliest memories is of him sitting on the couch holding the newspaper, and me, knocking on the front page like a door: Attention, please. My friends and I got used to Hawk Eye reporters milling around, documenting our softball games and school musicals—there was the writer with the beard, the photographer with the ponytail. And every four years, when the men who wanted to be president rolled into town, Hawk Eye reporters asked us what we thought of them. The newspaper was omnipresent; it had been for nearly 200 years. The Hawk Eye is considered the oldest newspaper in the state, but technically, it began as two separate ones. The Wisconsin Territorial Gazette and the Burlington Hawk-Eye were founded in the mid-19th century by a pair of bitter political rivals. The delicate yellowed pages of those early editions contain stories about area Whig conventions and ads for newfangled steel plows. During the Great Depression the two papers became one: the Burlington Hawk-Eye Gazette. A few years later, the Harrises, a wealthy Kansas family, added it to their collection of midwestern dailies. The Harrises encouraged editorial independence; they didn’t hover. They wanted The Hawk Eye to be local. The paper’s reporters wrote about the boys from nearby towns who went to fight the Nazis, and the Vietnam War protest at the Des Moines County courthouse. The Hawk Eye had influence: John McCormally, who edited the paper in the 1960s and ’70s, was the first editor in Iowa, and probably in the country, to endorse Jimmy Carter for president, a move that contributed to Carter’s victory in the Iowa caucuses. By the time my parents moved to town in the early 1980s, The Hawk Eye had already won Best Newspaper in Iowa three times, Alison told me. My parents took out a subscription, and followed along as Hawk Eye reporters covered big regional stories: the murder of Mount Pleasant Mayor Edd King; the 500-year flood of 1993; the 500-year flood of 2008; the 2015 killing of a woman named Autumn Steele, who was accidentally shot by a police officer and whose death led to a years-long fight between the newspaper and the Burlington Police Department to make police records public. There were smaller items, too. A year before the grain-elevator explosion, The Hawk Eye covered Gloria Estefan leading the world’s longest conga line at the Steamboat Days festival. In 2002, Harrison Ford flew his helicopter to town and spent the night at a Burlington hotel. Asked how he liked chicken lips—a local restaurant staple—he told The Hawk Eye that they were just “OK.” As a kid, I liked the opinion pages best. I devoured Sweet’s columns about global warming and the Iraq War. In sixth grade, I started writing letters to the editor about the rampant alcohol consumption at the water park, the lackadaisical recycling program at my school, the cruel treatment of the fish in the aquariums at Walmart. Each letter, printed in the op-ed section, included my name and my age: “By Elaine Godfrey, 12.” Over the years, my parents became friendly with Sweet. Once, during dinner at his house, he made me promise that I’d never be a reporter. The pay was terrible, he said, and the future of journalism wasn’t looking so great. I swore that I wouldn’t. In late April, I pulled up in my rental car to the Burlington Amtrak station, situated just off Main Street, only a few hundred yards from The Hawk Eye’s offices. The depot overlooks the Mississippi River. Sometimes bald eagles fly by carrying fish. Dale Alison and a few other former staffers who had been meeting at the station occasionally for coffee during the pandemic met me there, including Sweet and the onetime business editor Rex Troute. I brought a box of Casey’s doughnuts and we talked about the paper’s slow death while trains packed with coal and grain rattled by. The collapse of Iowa’s oldest newspaper, they told me, began with a staff-wide announcement in November 2016: A publishing company called GateHouse, run by an investment firm in New York, was the buyer. GateHouse had already bought 121 daily papers, 316 weeklies, and 117 supermarket circulars across the country. It was a good time for gobbling up newspapers: Companies could buy them cheap, centralize resources, and slash staff to make a profit. But GateHouse reassured them that things would not change much in the newsroom. “You have a great legacy here. We want to keep that going,” a GateHouse editor told the staff. “GateHouse buys papers to make communities better.” After three months, Sweet retired. Steve Delaney, who had become the paper’s publisher, was fired in April 2017. Alison, by then the managing editor, was let go in June, along with several others. Rex Troute retired then, too. The copy desk took buyouts that summer, and their duties were moved to Austin, Texas. Over the next two years, more reporters accepted buyouts, most of the paper’s advertising roles were eliminated, the six-person press crew was dissolved, and printing operations were moved to Peoria. In 2019, GateHouse bought USA Today publisher Gannett and took its more well-known name. At the time, Gannett owned more than 100 daily papers, and after the merger, the company owned one out of every six newspapers in the country. The Hawk Eye, which started 2016 with 100 people on the payroll, today has about a dozen. From the depot, the newspaper veterans and I had a decent view of the boxy brown Hawk Eye office. Gannett had put the building up for sale last winter. Readers noticed the paper’s sloppiness first—how there seemed to be twice as many typos as before, and how sometimes the articles would end mid-sentence instead of continuing after the jump. The newspaper’s remaining reporters are overworked; there are local stories they’d like to tell but don’t have the bandwidth to cover. The Hawk Eye’s current staff is facing the impossible task of keeping a historic newspaper alive while its owner is attempting to squeeze it dry. None of this was inevitable: At the time of the sale to GateHouse, The Hawk Eye wasn’t struggling financially. Far from it. In the years leading up to the sale, the paper was seeing profit margins ranging from the mid-teens to the high 20s. Gannett has dedicated much of its revenue to servicing and paying off loans associated with the merger, rather than reinvesting in local journalism. Which is to say that southeastern Iowans are losing their community paper not because it was a failing business, but because a massive media-holding company has investors to please and debts to pay. (A Gannett representative acknowledged that the company has prioritized repaying its creditors, but said that it is committed to supporting local journalism.) I thought about the consequences of the paper’s decline when I visited the cluttered archives room at the Burlington Public Library this summer. Rhonda Frevert, a librarian who writes a monthly column for The Hawk Eye, reminded me that the paper is more than a guide to local happenings: It’s a repository of community knowledge. People come to search the archives for birth announcements, obituaries, stories about their families, and businesses that used to be in town. When those stories aren’t written, they’re not kept anywhere. There’s no record. For the past several decades, The Hawk Eye’s owners donated bound copies of the newspaper to the library on a regular basis. Suddenly, three years ago, they stopped; the new owners were no longer providing that service. The library's archives simply end in January 2019, the last of the paper’s physical record marked by a thin metal bookend. In early spring, I joined a Facebook group called “Burlington (IOWA) Breaking News reports and MORE” and realized that many of my high-school classmates were already members. So were my mom and most of her friends. The group has more than 16,000 people in it—more than triple the number of people who subscribe to The Hawk Eye. It’s ostensibly a site for sharing news about the community, but the page is chaotic. Scroll down and you’ll find mug shots of tattooed men alongside pictures of missing dogs, ads for rib eyes at Fareway, and comments accidentally made in all caps. I found more of the same in other Facebook groups, including “Greater Burlington IA Uncensored Chat” and “Greater Burlington (Iowa) Neighborhood Chatter.” The pages can be a useful resource, and a good source of community jokes and gossip. But speculation and rumor run rampant. A member might ask about a new building going up in town, and someone will guess that it will be an Olive Garden. It never is. When a member hears something that sounds like gunshots nearby, she’ll post about it, and others will offer theories about the source. Once, I read a thread about an elementary-school principal suddenly skipping town. Some thought he might have behaved inappropriately with a student; one person said he’d been involved with a student’s mother; another swore they’d seen security-camera footage of the principal slashing tires in a parking lot at night. I checked The Hawk Eye and other outlets, but I couldn’t find verification of any of those stories. Alison is a member of “Burlington Breaking News,” and all of the guessing is hard for him to watch. He often interjects in the comments to correct false information. Sometimes he posts news himself. “The stop light at Gear Avenue and Agency Street isn't expected to be working until spring,” he announced late last winter. People want to know what’s going on, Alison told me; they just don’t know how to find the answer, whom to call, where to look. That’s what reporters are for. In the absence of local coverage, all news becomes national news: Instead of reading about local policy decisions, people read about the blacklisting of Dr. Seuss books. Instead of learning about their own local candidates, they consume angry takes about Marjorie Taylor Greene. Tom Courtney, a Democrat and four-term former state senator from Burlington, made more than 10,000 phone calls to voters during his 2020 run for office. In those calls, he heard something he never had before: “People that live in small-town rural Iowa [said] they wouldn’t vote for me or any Democrat because I’m in the same party as AOC,” Courtney told me. “Where did they get that? Not local news!” Courtney lost in November. It’s difficult to quantify that creeping sense of disconnection, those crumbling social ties. But southeastern Iowans feel it, and they’ll describe it if you ask them to. Within hours of posting in “Burlington Breaking News” to ask for people’s thoughts on The Hawk Eye, I received dozens of comments, emails, and private Facebook messages. Almost everyone expressed sadness about the paper’s deterioration. “We feel like we’re all little islands out here,” Deb Bowen, a 72-year-old Burlington resident, told me on the phone. Jon Billups, the city’s current mayor, worked as The Hawk Eye’s circulation director after closing his family’s tire shop. But GateHouse fired him in 2017. Since the purchase of the paper, he’s noticed a growing negative self-image among residents, he told me. Fewer people see Burlington as a nice place to live; they seem to like their neighbors less. “We’re struggling with not having [this] iconic thing.” As mayor, he helped start a newsletter to keep residents updated on city projects. “It’s a matter of time before our local paper does not exist,” he told me. In 2018, Hawk Eye alumnus Jeff Abell founded a new online newspaper called the Burlington Beacon to help fill the void, and soon brought on another former Hawk Eye reporter, William Smith. They post articles straight to Facebook and have launched a weekly print edition for subscribers. But the Beacon is far from profitable. Until recently, Abell paid Smith from his own pocket. The two work out of Abell’s comic-book store in downtown Burlington. At the depot, I asked Alison what he thought about the Beacon’s prospects. “Jeff and Will are doing their best,” he said. “But doggone it, it would take 150 years to build up what they had here.” Last fall, a man named Gary posted on the “Burlington Breaking News” page, asking: “Anyone know what is going to be built at Broadway and Division south of the Girl Scout office?” A construction crew had recently broken ground at the site. People in the Facebook group started to weigh in: Maybe it’ll be a new sandwich joint; that’d be nice. Maybe a coffee shop, or a Dollar Tree, or another bank. Someone had heard that it might be a dentist’s office. One of the page’s moderators suggested that perhaps it was a new spec building that would soon be put up for sale. Then the thread ended. The Hawk Eye never ran a story about the new building. Soon, the post was forgotten, buried under a mounting pile of questions from other southeastern Iowans wondering what, exactly, was going on in town.