Janine Jackson interviewed Public Citizen’s Robert Weissman about the Boeing scandal for the March 29, 2024, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

Janine Jackson: Boeing CEO David Calhoun is going to “step down in wake of ongoing safety problems,” as headlines have it, or amid “737 MAX struggles,” or elsewhere “mishaps.”

Had you or I at our job made choices, repeatedly, that took the lives of 346 people and endangered others, I doubt media would describe us as “stepping down amid troubles.” But crimes of capitalism are “accidents” for the corporate press, while the person stealing baby formula from the 7-Eleven is a bad person, as well as a societal danger.

There are many reasons that corporate news media treat corporate crime differently than so-called “street crime,” but none of them are excuses we need to accept.

Public Citizen looks at the same events and information that the press does, but from a bottom-up, people-first perspective. We’re joined now by the president of Public Citizen; welcome back to CounterSpin, Robert Weissman.

Robert Weissman: Hey, it’s great to be with you.

JJ: Boeing is a megacorporation. It has contractors across the country and federal subsidies out the wazoo, but when it does something catastrophic, somehow this one guy stepping down is problem solved? What happened here versus what, from a consumer-protection perspective, you think should have happened, or should happen?

RW: Well, I think the story is still being written. Folks will remember that Boeing was responsible for two large airliner crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed around 350 people. The result of that, as a law enforcement matter, was that Boeing agreed to a leniency deal on a single count of fraud. It didn’t actually plead guilty; it just stipulated that the facts might be true, and promised that they would follow the law in the future. That agreement was concluded in the waning days of the Trump administration.

Fast forward, people will remember the recent disaster with another Boeing flight for Alaska Airlines earlier this year, when a door plug came untethered and people were jeopardized. Luckily, no one was fatally injured in that disaster.

But the disaster itself was exactly a consequence of Boeing’s culture of not attending to safety, a departure from the historic orientation of the corporation, and, from our point of view, directly a result of the slap-on-the-wrist leniency agreement that they had entered after the gigantic crashes of just a few years prior.

So now the Department of Justice is looking at this problem again. They are criminally investigating Boeing for the most recent problem with Alaska Airlines Flight 1282. And we are encouraging, and we think they are, looking back at the prior agreement, because the prior agreement said, if Boeing engages in other kinds of wrongdoing in the future, the Department of Justice can reopen the original case and prosecute them more fully–which it should have done, of course, in the initial instance.

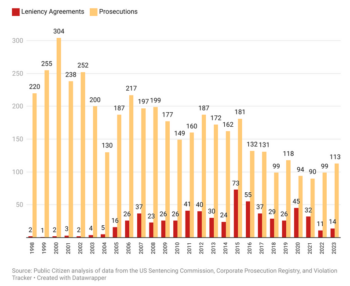

JJ: Let’s talk about the DoJ. I’m seeing this new report from Public Citizen about federal corporate crime prosecutions, which we think would be entertained in this case, and particularly a careful look back at choices, conscious choices, made by the company that resulted in these harms. And this report says the DoJ is doing slightly more in terms of going after corporate offenders, but maybe nothing to write home about.

RW: Right. There was a very notable shift in rhetoric from the top of the DoJ at the start of the Biden administration, and not the normal thing you would hear. Much more aggressive language about corporate crime, and holding corporations accountable, and holding CEOs and executives accountable.

However, that rhetoric hasn’t been matched in good policymaking, and we had the lowest levels of corporate criminal enforcement in decades in the first year of the administration. We gave them a pass on that, because that was mostly carrying forward with cases that were started, or not started, under the Trump administration. But we’ve only seen a slow uptick in the last couple years. So it has increased from its previous low, but by historic standards, it’s still at a very low level, in terms of aggregate number of corporate criminal prosecutions.

By the way, if people are wondering, what numbers are we talking about, we’re talking about 113. So very, very few corporate criminal prosecutions, as compared to the zillions of prosecutions of individuals, as you rightly juxtaposed at the start.

JJ: And then even, historically, there were more corporate crime prosecutions 20 years ago, and it’s not like the world ended. It didn’t drive the economy into the ground. This is a thing that can happen.

Robert Weissman: “There’s no sense in which holding corporations accountable for following the law is going to interfere with the functioning of the economy.”

RW: Correct. The corporate criminal prosecutions don’t end the world, and moreover, corporate crime didn’t end. So we ought to have more prosecutions than we have now. I mean, we’re just talking about companies following the law. This is not about aggressive measures to hold them accountable for things that are legal but are wrong, which is, of course, pervasive. This is just a matter of following the law. There’s no sense in which holding corporations accountable for following the law is going to interfere with the functioning of the economy. It doesn’t diminish the ability of capitalism to carry out what it does. In fact, following the rule of law, for anyone who actually cares about a well-functioning capitalist society, should be a pretty core principle, and enforcement of law should be a core requirement.

JJ: And one thing that I thought notable, also, in this recent report is that small businesses are more likely to face prosecution. And that reminds me of the IRS saying, “Well, yeah, we go after low-income people who get the math wrong on their taxes, because rich people’s taxes are really complicated, you guys.” So there’s a way that even when the law is enforced, it’s not necessarily against the biggest offenders.

RW: Yeah, that’s right. Although the numbers are so small, that disparity isn’t quite that stark. I think the big thing that illustrates your point, though, is the entirely different way that corporate crime is treated than crime by individual offenders, street offenders.

First of all, the norm for many years has been reliance on leniency agreements. So not even plea deals, where a corporation pleads down, or a person might plea down the crime to which they are admitting guilt. But a no-plea deal, in which they just say, “Hey, we promise to follow the law going forward in the future, and if we do, you won’t prosecute us for the thing that we did wrong in the past.”

Human beings do not get those kinds of deals, except rarely, in the most low-level offenses. But that’s been the norm for corporations, for pervasive offenses with mass impacts on society, sometimes injured persons, and instances where the corporations, of course, are very intentional about what they’re doing, because it’s all designed based on risk/benefit decisions about how to make the most profit. The sentences and the punishments for corporations in the criminal space and for CEOs in the criminal space are just paltry.

JJ: So if deterrence, really genuinely preventing these kinds of things from happening again, if that were really the goal, then the process would look different.

RW: It would look radically different. I think that there’s a lot of data when it comes to so-called street crime. You need enforcement, obviously, against real wrongdoing, but tough penalties don’t actually work for deterrence. It’s just not what the system is, in terms of the social system and the cultural system, people deciding to follow or not follow the law and so on.

But for corporations, deterrence is everything. They are precisely profit-maximizing. They’re the ultimate rational actors. If the odds are good that they will be caught breaking the law and suffer serious penalties, then they will follow the law, almost to a T. So this is the space where deterrence actually would work, and we see criminal deterrence with aggressive enforcement and tough penalties really missing from the scene.

And this Boeing case is the perfect example. The company was responsible, through its lax safety processes, for two crashes that killed 350-plus people; they got off with a slap on the wrist. As a result, they didn’t really feel pressure to change what they were doing, and they put people at risk again. If they had been penalized in that first instance, I think you would’ve seen a radical shift in the company, much more adoption of a safety culture. We would have avoided this most recent mishap.

JJ: Let me, finally, just bring media back in. There was this damning report from the Federal Aviation Administration last month, and the reporting language across press accounts kind of incensed me.

This is just the Seattle Times: “A highly critical report,” they said, “said Boeing’s push to improve its safety culture has not taken hold at all levels of the company.” “The report,” the paper said, “cites ‘a disconnect’ between the rhetoric of Boeing’s senior management about prioritizing safety and how frontline employees perceive the reality.”

Well, this is Corporate Crime 101. I mean, there are books written on this. It’s not a disconnect: “Oh, the company’s at war with itself; leadership really wants safety really badly, but the workers just aren’t getting it.”

This is pushing accountability down and maintaining deniability at the top. So the CEO doesn’t have to say, “Oh, don’t follow best practices here.” They just need to say, “Well, we just need to cut costs this quarter,” and everybody understands what that means. Anybody who’s worked in a corporation understands what “corporate climate” means.

And so I guess my hopes for appropriate media coverage dim a little bit when there is so much pretending that we don’t know how decision-making works in corporations, that we don’t know how corporations work, when I know that reporters do.

RW: Yeah, well, I’ll just say that is so 100% correct in characterizing what happened at Boeing, because not only is that fake, and obviously culture is set from the top, this is a place where the culture of the workers and the engineers wants to, and long did, prioritize safety. They’re the ones who’ve been calling attention to all the problems. So it’s management that’s preventing them from doing their jobs, which is what they want to do.

I think in terms of how media talks about this, I agree with your point, and I think the reporting on Boeing has been pretty good in terms of documenting what happened. But what is often missing from even really good reports in mainstream news media is the criminal justice frame.

Now, admittedly, that partially follows from the failure of the Department of Justice to treat it as a criminal matter seriously, but I think it does change the way people think about this stuff. If you call it a crime, it’s exactly as you said, it’s not errors, it’s not just lapses. It’s certainly not mistakes. These are crimes, and they’re crimes with really serious consequences, in this case, hundreds of people dying.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Rob Weissman, president of Public Citizen. You can find their work on Boeing and many, many other issues online at citizen.org. Robert Weissman, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

RW: Great to be with you. Thanks so much.