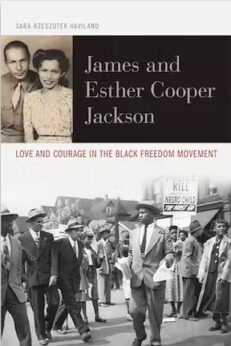

James and Esther with their daughters Kathryn (left) and Harriet (right), circa 1960s., Family collection

Esther Cooper Jackson was part of an “astonishingly excellent cohort of Black women of an earlier generation, including Claudia Jones; Shirley Graham; Louise Patterson; and Dorothy Burnham – who is still with us (fortunately) at the age of 108 – who will serve as role models and inspirations for all of us but especially Black girls, for generations to come” noted historian Gerald Horne.

Jackson, long-time activist, writer, and editor died on August 23, 2022 – two days after her 105th birthday. Although her health had recently been failing, she remained intellectually sharp, witty, and eager to engage in discussions on national and international affairs. Jackson’s life illustrated and reflected the 20th-century struggle for African-American equality, democracy, and world peace. Her central roles in the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC), the Civil Rights Congress, the Committee to Defend Negro Leadership, and Freedomways magazine have cemented her place in history.

Horne continued: “A giant has fallen and, as often said, when an elder of note has expired, an entire library has been buried with her. Her foundational role with Freedomways, perhaps the most significant periodical of the anti-Jim Crow movement should never be forgotten.”

As the founding editor of Freedomways, Esther Cooper Jackson helped create one of the most significant publications of the radical Black left in the 1960s, and mentored countless others who were involved in the milieu of the magazine, Ian Rocksborough-Smith from the University of the Fraser Valley in S’ólh Téméxw/British Columbia, Canada told People’s World.

“From her over 25 years as editor of Freedomways magazine, she gave the liberation struggles and movements across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Latin America, and the United States a beacon light. She gave old and newer voices a place to write and be heard,” said Maurice Jackson, a close friend of the Jacksons and a professor at Georgetown University.

Esther Cooper was born in Arlington, Virginia on August 21, 1917. Her mother, Esther Georgia Irving Cooper, was president of the Arlington NAACP and active in the struggle against educational discrimination. Jackson attended the segregated schools of Arlington before graduating from Oberlin College in Ohio and later earning a master’s degree in sociology from Fisk University. Her master’s thesis, entitled “The Negro Woman Domestic Worker in Relation to Trade Unionism,” is cited by scholars as one of the first sociological studies on African American women workers.

She then planned to enroll in a Ph.D. program in sociology at the University of Chicago and could have easily proceeded to the relatively comfortable world of an academic, but instead decided to join the Southern Negro Youth Congress’s Voting Project. Through her affiliation with SNYC she met and married her future husband, Dr. James E. Jackson. Thus, began decades of work in the struggle for equality, democracy, and peace.

For years, Esther Cooper Jackson traveled throughout Alabama organizing the struggle for voting rights and an end to racial segregation. Over the course of those travels, she worked closely with individuals who would years later form the Alabama Christian Movement as well as other activists including Louis Burnham, Jack O’Dell, Ed and Augusta Strong, and Sallye and Frank Davis.

The late civil rights activist Julian Bond once noted that the Jacksons and their co-workers “organized the Southern Negro Youth Congress decades before SNCC spearheaded the civil rights movement of the 1960s. SNYC was a model of what Black youth should and ought to do,” Bond said, and “preceded us, dared as we dared, dreamed as we dreamed.”

While James Jackson served in the U.S. military during World War II, Esther continued her organizing activities in the South. After the war, the Jacksons moved to Detroit, where James participated in educational work on behalf of the Communist Party among Detroit autoworkers and Esther became active in the Civil Rights Congress. In the CRC, Esther helped lead the fight to defend leaders of the Communist Party against McCarthyite persecution. Her husband James was targeted by the U.S. government and went underground for five years. Esther was left to raise their two children while, at the same time, organizing against McCarthyite repression.

She was also among the leaders in the struggle to defend Rosa Lee Ingram, an African American woman in Georgia who, along with two of her sons, was convicted of murder in the death of a white sharecropper who had assaulted her.

As James emerged from the underground, he stood trial and was convicted, but the conviction was overturned before he served any prison time.

In the early 1960s, the Jacksons moved to New York City. James took on a national leadership role in the Communist Party and Esther began working with activists – including Shirley Graham Du Bois, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Paul Robeson – to launch the publication Freedomways. From 1961-1985, Esther was the managing editor of this influential magazine which covered politics, international affairs, and culture within the context of African-American history.

Activists and scholars from across the country paid tribute to Esther Cooper Jackson on her death.

Maurice Jackson told People’s World: “Esther Cooper Jackson, was the Soul of Black Folks, the Soul of Humanity – the Salt of the Earth. From her days at Washington’s historic Dunbar High School to Oberlin and to Fisk University, she fought for equality. From her cofounding of the Southern Negro Youth Congress she was a warrior for justice. During the fascist-like McCarthy era, she stood as a woman of enormous courage, saying that she and Jack ‘devoted ourselves to each other, to our daughters, and to the great cause of our times’ through thick and thin. Hers was a ‘life supreme,’ where throughout her century plus five years she emitted a love supreme, for humankind. Nothing could be finer.”

Frank Chapman, executive director of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, said he met Esther Jackson in 1963, just two years after he had been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to life and 50 years in the Missouri State Prison. “What inspired me to write her was a fellow prisoner who gave me a copy of Freedomways.” Three years later, in the summer of 1966, Freedomways published an article Chapman had written titled, “Mathematics in Antiquity or Science and Africa.” “Esther helped my case in getting national attention,” Chapman said. “Also, this was the beginning of a relationship with Esther and Jim Jackson that stayed with me throughout the time I was in prison (13 more years after 1963) and until now, almost 58 years later.” Chapman called Esther Jackson “a long-distance warrior for freedom.”

Sara Rzeszutek Haviland, the Jacksons’ biographer, added, “It is difficult to quantify Esther Cooper Jackson’s contributions to the Black freedom movement. In addition to being an incredibly important activist, she welcomed everyone she met with warmth, generosity, and an unforgettable smile. She will be sorely missed by all who knew her.”

Toward the end of her life, Esther Jackson began to receive the attention she deserved. Haviland analyzed the Jacksons’ contribution to the struggle for democracy in James and Esther Cooper Jackson: Love and Courage in the Black Freedom Movement. (University Press of Kentucky, 2015.) Esther was frequently asked to lecture at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Toward the end of her life, Esther Jackson began to receive the attention she deserved. Haviland analyzed the Jacksons’ contribution to the struggle for democracy in James and Esther Cooper Jackson: Love and Courage in the Black Freedom Movement. (University Press of Kentucky, 2015.) Esther was frequently asked to lecture at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

In 2006, New York University’s Tamiment Library received the Jacksons’ archive. A symposium heralding this important acquisition was held in October 2006. The proceedings were published as Red Activists and Black Freedom: James and Esther Jackson and the Long Civil Right Revolution (Routledge, 2010.) The symposium featured scholars and activists, including David Levering Lewis, Robin D.G. Kelley, Maurice Jackson, and Angela Davis.

Esther Cooper Jackson’s life is an example of a life well lived. One that was dedicated to the betterment of the society and the world in which she was born.

Esther Cooper Jackson – Presente!

Timothy V Johnson is a member of the African American Equality Commission of the CPUSA.