Government-backed development projects line the pockets of few to the detriment of most, the Madison-based journalist says in a new book.

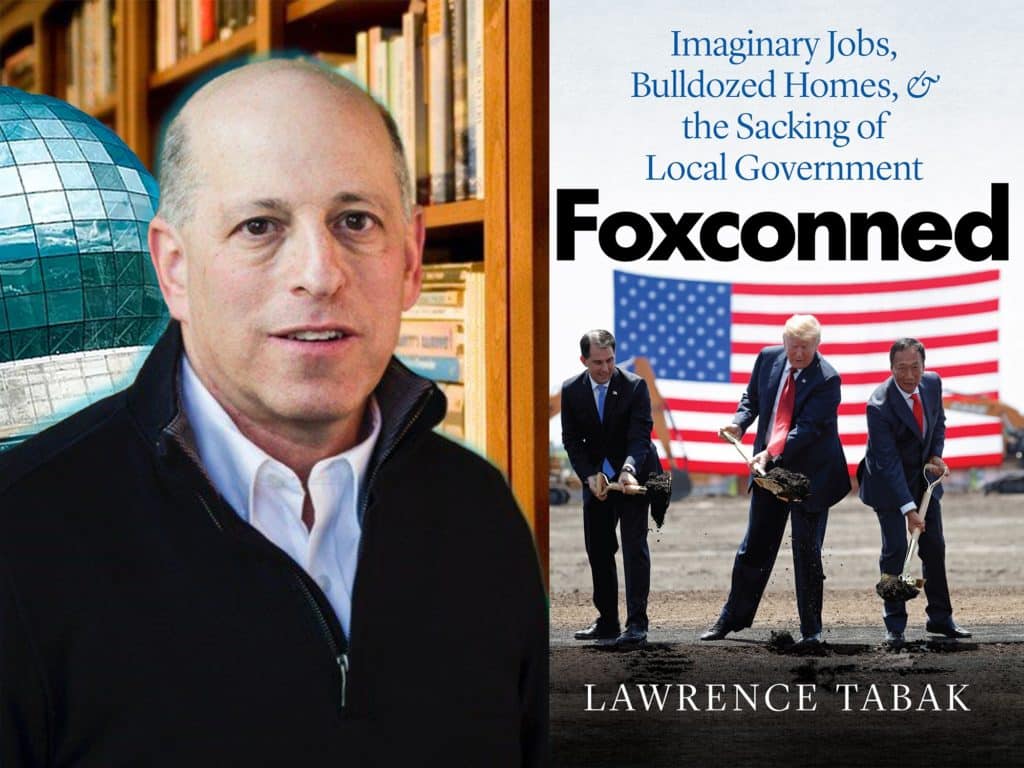

Header image: A portrait of Lawrence Tabak, along with the cover of his book “Foxconned.” The orb-shaped building from Foxconn’s Wisconsin campus is superimposed behind Tabak.

In 2017, former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker signed a now-infamous deal with Taiwanese electronics giant Foxconn to build a large-screen LCD factory that would, backers claimed at the time, provide 30,000 to 50,000 jobs. It would also need a healthy amount of local funding support. That same year, Walker’s Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation had a $34 million operating budget. Ninety percent of its funds came from taxpayers. Two-thirds of the budget was slotted for salaries and operating expenses.

Around the same time, the tiny Village of Mount Pleasant, near Racine, funded $764 million in municipal debt to welcome Foxconn. Mount Pleasant’s part-time, Tea Party-dominated village board made the call with no input from public hearings or referendums, yet with ample advice from high-priced development consultants. It then set about razing family farms and other homes, declared blighted so they could be taken by eminent domain. The state gave up its wetlands jurisdiction over the site and stripped environmental regulations to allow for more water and air pollution.

Foxconn’s Wisconsin campus would be the Eighth Wonder of the World, a grandstanding President Donald Trump promised at a groundbreaking ceremony in 2018. But LCD screens have never been commercially produced in the Western Hemisphere, let alone in the United States. Foxconn’s LCD screens are manufactured in less-regulated places like China by low-wage workers in such poor conditions that windows have nets outside them to catch jumpers. The project, enthusiastically greenlighted by a Republican state legislature, left Wisconsin embarrassingly swindled. Foxconn’s purported business plan in Wisconsin has changed multiple times. Furthermore, it perpetuated widening wealth disparities.

Flash forward to December 2021. A “Potemkin TV factory,” as Madison-based journalist Lawrence Tabak calls it, sits on the Foxconn site with a few unused buildings. The promised jobs are nowhere to be found. In his recently published book Foxconned: Imaginary Jobs, Bulldozed Homes And The Sacking of Local Government (2021, University of Chicago Press), Tabak recounts the Wisconsin-Foxconn timeline in excruciating detail. It unfolds like a political horror movie recounted too soon for comfort and too late for anything to be done about it. It’s a cautionary tale for other states and even countries to avoid.

Tabak, who grew up in Dubuque, wrote about the Foxconn deal for the Midwestern regional publication Belt Magazine before expanding his efforts into the book—publishing some of the most aggressive and insightful reporting anyone’s done to date on the project. Tone Madison caught up with Tabak in December.

Tone Madison: Let’s talk a little bit about what you call “the government institutionalization of economic development.”

Lawrence Tabak: Economic development has become a growth industry. If you look back 30 or 40 years, it was maybe a side function of someone in civic government. Now, there are large enterprises like the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation, which spends most of their energy in trying to land new corporate and industrial development. The problem is that everyone has one of these agencies. And so they’re all competing against each other. So you have a case, as in Foxconn, where the bidding just kept going up. Wisconsin was bidding against seven other states. And the end result is sort of a race to the bottom, because if this Foxconn plant was really a necessity for that company to create a North American industrial center, they would do it with or without the incentives. The incentives will not make an enterprise that’s not feasible work. Turns out that the plant that they had proposed was not feasible. There’s never been a large screen television-type screen factory in the Western Hemisphere. And there’s reasons for that, and that involves supply chain cost of development, labor costs, and from the beginning, I was skeptical that those could be surmounted. And it turned out they couldn’t.

Tone Madison: You said that there was scrutiny in different U.S. regions bidding against one another. Who was this scrutiny coming from?

Lawrence Tabak: Well, I think it was more the fact that when you started hitting billions of dollars of incentives, the spotlight was just being shone on the process. The fact that there are thousands of these [projects] being done at the million dollar level, or the $10 million level, is less visible to people. So I don’t think there was a lot of really deep rethinking of this. Because it would require a national revision of how we do our economic development, because this thing has grown gradually over many years, decades.

Tone Madison: Has anything changed in the whole Foxconn situation since you wrote this book?

Lawrence Tabak: Foxconn built a couple of large warehouse-type buildings and put up what they call a disco ball-type of building, which is kind of flashy, not particularly large, and a building for unknown purposes, but there isn’t really any industrial action in those areas. They were making face masks for a while in Racine County, during the pandemic, which was a nice thing to do, but it was hardly a billion dollar enterprise. So all of this land remains available for development either by Foxconn, which now owns about 1,000 acres of this land, or the Village of Mount Pleasant, which has now become one of the largest landholders in Southeastern Wisconsin. So there’s not much going on there in terms of actual business development. I think the local officials are optimistic that sooner or later, they’ll be able to convince some kind of development to come into that area. After all, they’ve spent close to a billion dollars on infrastructure. It’s, as a result, an attractive industrial park with lots of electricity, water, wonderful roads that have no cars on them at the moment. And you know, they’re busy seeking tenants to come in, but no one’s really taken that bait.

The state has some real liabilities in this project, because in the legislation that Walker pushed through, the state took on the moral obligation of backing the bonds that were being issued by Racine County in the Village of Mount Pleasant, which have now totaled hundreds of millions of dollars. If they’re unable to pay back those bonds, the state has to step in and absorb about half of the cost of those bonds.

So that’s kind of a sword of Damocles hanging over the state of Wisconsin, to have this hundreds of millions of dollars of debt. And the only way that the municipalities can pay that back is if Foxconn continues to pay a significant amount of property tax. They’ve pledged to pay that property tax for 30 years, regardless of what they build. The assessed value that they’ve guaranteed is $2.3 billion worth of property. They have nowhere near that amount. When Governor Evers looked at that situation, he had plenty of incentive to work out a deal to keep Foxconn in the area, because the only hope of keeping this whole project solvent was to keep Foxconn in the area, paying taxes on their property. So re-writing of the contract was done not too long ago, which involved a promise of much fewer jobs from Foxconn, involved much lower incentives from the state and was, I believe, intended to create an atmosphere where Foxconn would be [incentivized] to hang around and continue to pay taxes.

Tone Madison: Do you have any projections or ideas about what the repercussions of the Foxconn situation will be in the medium and longer terms?

Lawrence Tabak: Well, this Foxconn case study is really a cautionary tale. But it’s not alone. You might recall the Amazon headquarters bidding that took place not too long after this in the following year, in which communities were willing to put up billions of dollars for this prize of an Amazon headquarters, which was actually a much bigger potential development. I mean, they were talking about 50,000 high-paid jobs. New York ended up putting up some money for that, and then taking it away. It was kind of a mess. And under the sort of the spotlight of these huge developments, I think there was a new sort of scrutiny of what we were doing in the United States in terms of really spinning our wheels, having one region bid against another, creating a flow of money from public coffers, to corporations, who, by every sort of study, an indication that’s available would still go ahead with their projects, if they were economically viable.

Guess what? Amazon started building a headquarters in New York despite the lack of the incentives, because there were reasons to build it there. And if Foxconn really needed a North American plant to build large-screen TVs, they would go ahead and do that, regardless of incentives. It just is, as it turns out, a way to subvert public monies into private hands, and not just corporations. But all of the contractors who tend to be, you know, cozy insiders, who have already made out quite well on the infrastructure spending. This has been going on in Racine County, you know, hundreds of millions of dollars of highways, of electrical infrastructure. Consultants coming in and pulling out millions of dollars out of the pool of money that’s been raised. It’s a benefit to a few at the cost of the many.

I hope people will have second thoughts about mixing politics with economic development. This all goes back to creating jobs and being able to brag about job creation… Venture capital in the United States would not have come to this cost, because they would look deeply into it and have said, “This is not looking like a viable industrial development. Why would I put my money into it?” Nevertheless, if you’re a taxpayer in Wisconsin, someone made the decision to put your money into it.

This kind of mismanagement and transfer of public funds to contractors and to corporations has a cumulative effect. That is part of the entire trend of income imbalance and wealth disparity that’s tearing the country apart. It’s not incidental, it’s at the heart of what’s likely to be our major challenges over the next years. And you have to start looking at what’s going on and what’s powering this. There are a lot of institutionalized forces and their interests are to keep it going. They don’t want to change anything. They’re living high on the hog. So we have, we have challenges.

You know, it’s not a story just about a bad project in Southeastern Wisconsin. It’s about an endemic problem across the country that’s contributing to some of the most serious problems that we face as a democratic society.