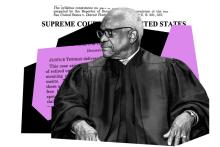

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. We’re working to change the way the media covers the Supreme Court. Sign up for the pop-up newsletter to receive our latest updates, and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

Many people watching Supreme Court opinions on Thursday may have breathed a sigh of relief as the court did not hand down any of the most-watched remaining cases (like the challenge to the president’s student debt relief program, or the challenge to affirmative action, or the challenge to LGBTQ equality and nondiscrimination protections).

But that’s only because a lot of people may have not been following the slow-motion disaster that has been unfolding in one of the less followed cases, Jones v. Hendrix. Jones involves a highly technical sounding, but practically significant, issue about when federal courts may correct wrongful convictions and wrongful sentences.

Essentially the case involves this scenario: What if it turns out that the federal courts that heard your criminal case made a mistake? And as a result of the courts’ mistake, you were convicted of something that isn’t actually a crime at all (because federal law doesn’t prohibit what you did), or, as a result of the courts’ mistake, you were sentenced to more time in prison than the law says you can be sentenced to? Can a federal court later correct the error in a federal habeas corpus proceeding when you challenge your conviction or sentence?

Today, the court, in a 6–3 opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, answered that question with a no. For people watching this catastrophe happen in real time, the result is not surprising. But it is a catastrophe nonetheless. As Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote in her powerful dissent, the opinion “unjustifiably closes off all avenues for certain defendants to secure meaningful consideration of their innocence claims.”

As a result of this opinion, people with illegal convictions and sentences—people who are legally innocent—will be stuck in prison for no good reason because the courts screwed up, not because they did. The law certainly did not require this result. And the Jones debacle carries a few warnings about the nightmare at One First Street.

One is that the Jones majority is part of a larger trend of the Supreme Court believing that the court (and all federal courts) are above reproach and can do no wrong. Take Justice Samuel Alito’s Wall Street Journal op-ed on Tuesday night, the one that insisted he was entitled to take free personal jet trips from hedge fund billionaires with business before the court (and also to not disclose said trips) because otherwise the personal jet seat would have gone empty. Or look at the months of gaslighting about how the influence and access campaign directed at the court’s Republican-appointed justices is all well and good because of course the justices are above reproach.

Jones is part of this trend. The cases affected by Jones are instances where a federal court screwed up. The federal court interpreted a statute incorrectly, and as a result, the court sent someone to prison for something that isn’t a federal crime. Or they sent someone to prison for more time than the law actually imposes on that person. Then, when a court later recognizes the error in some other case, the incarcerated individual asks the court to fix the mistake in their case and to let them out of prison.

Justice Thomas’ six-justice majority basically shrugged its shoulders and said, “Too bad, so sad, we may have messed up, but you’re going to stay in prison.” As Justice Jackson wrote in her must-read dissent (which, as a disclosure, includes a citation to some of my work on this topic), the “implications of the nothing-to-see-here approach that the majority takes with respect to the incarceration of potential legal innocents” are pretty ghastly. “Apparently,” she observed, “legally innocent or not, Jones must just carry on in prison regardless.”

It’s not overstating things to say that this opinion means that there are people who are in prison illegally, but now have no vehicle to seek their release from a federal court. As Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan wrote in a rare joint dissent, “A prisoner who is actually innocent, imprisoned for conduct that Congress did not criminalize, is forever barred … from raising that claim, merely because he previously sought postconviction relief.”

Yikes. And that brings me to my second point, which is that the case is part of a disturbing pattern of Republican appointees overvaluing the finality of criminal convictions rather than the lawfulness of criminal convictions, and the related trend of the Republican appointees narrowing the availability of remedies to enforce people’s rights. Again this issue is super technical, but this is how the relevant body of federal law works. For people who are convicted in federal court, after they finish their appeals, federal law allows them to file a section 2255 motion to challenge their conviction or sentence (perhaps on the basis of newly discovered evidence, perhaps on the basis of a new federal decision, or perhaps on grounds they couldn’t raise during their appeal, such as ineffective assistance of counsel). But under the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, federal law severely restricts their ability to file a second or successive 2255 motion; they can only do so on the basis of certain newly discovered evidence, or on the basis of a limited category of decisions about constitutional law.

That leaves out circumstances where a later decision on statutory law indicates that the courts misinterpreted a statute and caused someone to be wrongly convicted or sentenced. And so those individuals—who are legally innocent of a crime or who were given a wrongful sentence—have traditionally relied on another provision of federal law (known as the savings clause) that allows incarcerated persons who are “authorized to apply for relief” under section 2255 to file a federal habeas petition challenging their conviction or sentence if section 2255 “is inadequate or ineffective to test the legality of [their] detention.” This is the avenue the court cut off on Thursday.

As Sotomayor and Kagan wrote in their joint dissent, where section 2255 bars a claim that could be raised in a habeas proceeding (like the claim that you’re innocent because the courts screwed up in interpreting a statute), section 2255 is inadequate to test a conviction and sentence because section 2255 doesn’t authorize a person to apply for relief—and so that person should be able to file a habeas petition. And as Jackson painstakingly documented, the legislative context, statutory design, body of case law leading up the enactment of AEDPA, and more than a few principles of constitutional law point toward the same conclusion—that claims of legal innocence (or statutory innocence as she alternatively calls them) should be able to be raised in federal habeas proceedings even if an individual has filed multiple post-conviction motions.

The majority arrived at the opposite conclusion by relying on a weird, negative inference from the federal statute. Essentially, they said, if Congress wanted to authorize people to file a second or successive motion when a federal court messed up on a statutory issue, it would have said so. And to permit individuals to file habeas petitions raising arguments that Congress didn’t allow them to raise in successive 2255 motions would mess up the whole system and allow too many people to file too many claims. The reasoning calls to mind one of Justice William J. Brennan’s famous lines from McCleskey v. Kemp: “Taken on its face, such [reasoning] seems to suggest a fear of too much justice.” Justice Thomas’ majority also relied on some pretty shoddy historical accounts of habeas corpus as well. (I’m sure they’ll get their history right one of these days.)

It’s also important to note the pattern here. Last term, in one of the more ghastly Supreme Court decisions, the same 6–3 majority from Jones ruled for Arizona in a case where the state had loudly and proudly argued that “innocence is not enough” to remedy a conviction for innocent persons convicted in state courts. In that case, incarcerated individuals sought to introduce evidence that they didn’t commit the crime they were convicted of, or were not even eligible for the death sentence they received. One of the individuals, Barry Jones, had successfully persuaded two federal courts (and four judges) that he probably didn’t commit the crime for which he had been sentenced to death. The court said too bad; it’s illegal for a federal court to consider evidence of his innocence, even if that evidence wasn’t ever introduced because the state appointed him an ineffective lawyer. After the 2022 midterm election resulted in a Democratic attorney general, Barry Jones successfully negotiated a plea agreement resulting in his release, though this Supreme Court would have allowed the state to execute him.

Today, the court continued down the same road, and is likely to continue further with no end in sight.

By Leah Litman

Add new comment