The participants of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, a forerunner of later freedom rides. From left: Worth Randle, Wally Nelson, Ernest Bromley, Jim Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin, Joe Felmet, George Houser, and Andrew Johnson, outside of NAACP lawyer Spottswood Robinson’s law office in Richmond, Va., on April 10, 1947. Courtesy of Walter Naegle

HILLSBOROUGH, N.C. — If you are or know of any relatives of Andy Johnson, who was last heard from while a student at the University of Cincinnati in the late 1940s, call the Orange County Courthouse in this town.

They should have a $25 check to refund a fine that Johnson paid in 1948. Be sure to ask for 75 years of interest.

Johnson, along with Joe Felmet, Bayard Rustin and Igal Roodenko, were convicted here of violating North Carolina’s segregation laws on a Trailways bus as it prepared to leave nearby Chapel Hill for Greensboro on April 13, 1947. Johnson, who was Black, and Felmet, his white seatmate, were arrested for sitting together, three seats behind the driver. As they were taken off the bus, Rustin, later a celebrated Black leader of the civil rights movement, and Roodenko, who was white and Jewish, rushed to take their place and were also arrested. Johnson paid the fine, but the other three did not, and ultimately served 22 days on a chain gang.

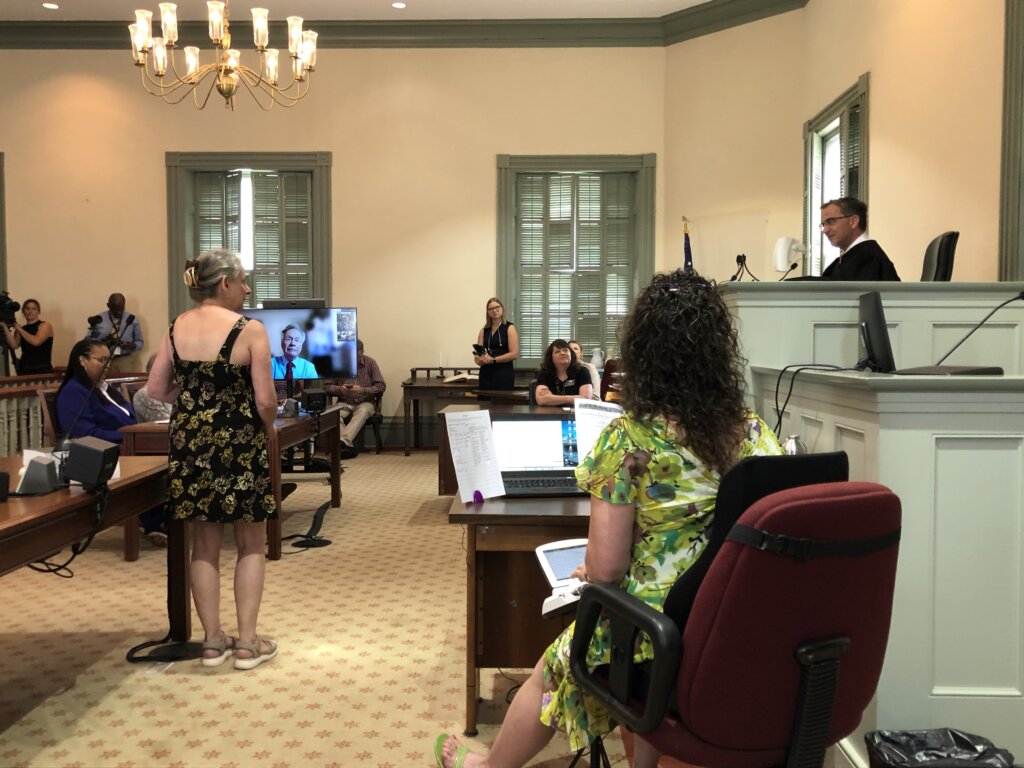

If that seems harsh, if not absolutely immoral, three-quarters of a century later, that same court now agrees. On Friday, Superior Court Judge Allen Baddour vacated their convictions and dismissed the charges, speaking from what officials say they believe is the same courtroom the men were convicted in. Along with present-day Chapel Hill Police Chief Chris Blue and other officials, Baddour apologized for the actions of their predecessors.

Noting that the riders’ arrests elsewhere in North Carolina did not result in convictions, Baddour said: “We failed in Orange County, in Chapel Hill. We failed to deliver justice in our community. And for that, I apologize. So we’re doing this today to right a wrong.”

Less than a decade after the convictions, segregation would be deemed a wrong by the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. But even in 1947, the high court had already determined the men were within their rights to sit side-by-side interracially. On June 3, 1946, the court deemed segregation in interstate transportation (but not intrastate) to be unconstitutional in Irene Morgan v. Virginia, a case centering on a Black interstate passenger who was a precursor to Rosa Parks.

The Southern states, however, refused to enforce that decision, leading 16 activists — eight Black and eight white, all men — from the Congress of Racial Equality and the Fellowship of Reconciliation to create the concept of a “freedom ride,” then called the Journey of Reconciliation. Deliberately sitting together in interracial pairs, they traveled throughout the Upper South, ostensibly free to do so as interstate passengers despite local segregation laws.

They were arrested numerous times throughout the two-week trip, which originated in Washington, D.C. on April 9. But only in Chapel Hill did they encounter violence, when a mob of white cabdrivers attacked them as they were being arrested. And only in Orange County N.C., were the charges sustained. A particularly ignoble moment came in the initial sentencing of Roodenko by Baddour’s long-ago predecessor in May 1947.

“Now Mr. Rodenky,” Rustin later recalled the judge saying, purposely mispronouncing Roodenko’s name. “It’s about time you white Jews from New York learned that you can’t come down here bringing your nigras with you to upset the customs of the South. Now, just to teach you a lesson, I have your Black boy 30 days on the chain gang, now I give you 90.”

Told the sentence would exceed the maximum punishment for the crime, the judge relented, ultimately leading Rustin, Roodenko and Felmet to serve 22 days of hard labor. Johnson, who was completing a thesis, said he was too busy and paid the fine instead.

That was the last the other riders heard from Johnson. Of the 16, most of the rest, like Rustin, who would gain fame as the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, went on to life-long careers as activists. And in what I had no idea would become a defining facet of my life, I got to know 10 of them 30 years ago, when I was blessed with the opportunity to produce a public television documentary about their trip, “You Don’t Have to Ride Jim Crow!” The film brought them back to the places they had visited nearly 50 years before.

It proved to be a race against time. Three riders died a month before we were scheduled to begin shooting. Another had a heart attack days before the first reunion trip. On the second trip, another forgot to bring his insulin.

Yet the film was completed, and aired nationally on PBS, as well as in hundreds of screenings nationwide, including one upcoming at Chapel Hill’s Chelsea Theater on June 27. That’s down the street from an official state marker at the site where the riders were arrested and attacked, dedicated in 2009. There are similar markers to Irene Morgan in Virginia, and other honors directly or indirectly from the documentary, most notably the presidential Medal of Freedom awarded posthumously to Rustin in 2013.

The idea for Friday’s action came from Renee Price, chair of the Orange County Board of Commissioners, who spoke at the dismissal event.

“We are here, 75 years later, to address an injustice and henceforth to correct the narrative regarding the Journey of Reconciliation and that segment of American history,” she said.

Baddour said Price originally envisioned correcting that injustice via a pardon from the governor. But while that would be allowed under the legal system, he said the party most responsible was the courts.

“One of the most important things for me was that this action be a judicial branch function,” he said. “It was our mistake, and it is our job to repair.”

In May, Baddour and his colleagues issued a statement accepting that responsibility.

“The Orange County Court was on the wrong side of the law in May 1947, and it was on the wrong side of history,” the statement read. “Today, we stand before our community on behalf of all five District Court Judges for Orange and Chatham Counties and accept the responsibility entrusted to us to do our part to eliminate racial disparities in our justice system.”

The legal correction comes too late for the riders: All those whose whereabouts were known since the 1940s have died, the last, Journey co-leader George Houser, at 99 in 2015. Given places of honor at the dismissal hearing were Rustin’s surviving partner, Walter Naegle, who appeared by Zoom, and Roodenko’s niece, Amy Zowniriw.

“The Journey of Reconciliation did not define my uncle,” Zowniriw said, noting that he always thought of her as “little Amy,” even after she was an adult.

“I would not be surprised if the people he served his sentence with here were not positively affected by knowing him,” she continued. “He devoted his life to changing the world for the better, sometimes one person at a time, and sometimes at great risk to his own personal well-being.”

Naegle also spoke of his personal connection.

“I knew two of these men — my partner Bayard Rustin, and Igal Roodenko. One was Black, the other was white. One was Quaker, the other Jewish. Both were gay. But they didn’t let these identities overshadow the larger identities they shared: as members of one human family,” Naegle said. “They were not fighting for their own group, if you will, but for all of us.”

Naegle’s Zoom appearance was necessitated by Thursday’s massive air travel failure, in which 1,500 flights were canceled, including mine before multiple rebookings. Zowniriw’s car broke down, and she and her husband had to rent one en route. Naegle managed to board a plane in New York, only for passengers to be ordered to disembark, and the flight scrubbed.

Referring to those woes, he told the 100-plus attendees: “I can assure you I did my best to get there. Perhaps next time I’ll take a bus.”

While that line brought laughter, there were also tears — including by the judge himself as he read the names of the four men. Granted a place of honor in the jury box, I too welled up, especially as I heard him unexpectedly praise the work I embarked on with a shoestring budget and seat-of-my-pants production 30 years ago.

“It’s an invaluable and important documentary, going back in history and teaching us all about these events, but also seeing these men interact as people, and humans, as humbles, as friends,” Baddour said. “It’s fabulous.”

For that, thank you. But the work isn’t done. Although we haven’t made contact yet, the court’s investigator, Rocky Smith, and I have identified relatives of Felmet, who died in 1994. And I wasn’t joking about finding those of Johnson’s, either — whether 75 years of interest is due or not.

Because their sacrifice should never be forgotten.