Smoke rises following an Israeli airstrike in Jabaliya refugee camp, northern Gaza Strip, on May 27, 2025. (Photo by Mahmoud Zaki/Xinhua via Getty Images)

DEIR AL-BALAH, GAZA STRIP—The genocide in Gaza is fast approaching 20 months since it began. My family and I have been displaced from our home in the Jabaliya refugee camp several times, but this is the first time we were forced to leave the north and flee south to Deir al-Balah, from where I am writing to you.

Living in Jabaliya had become impossible. By stripping us of our health and money, ongoing displacement has forced changes on us: from being a proud family to one that lives in humiliation. We were pushed south last month, during Israel’s fourth invasion of Jabaliya in mid-May. In preparation for yet another ground invasion, the Israeli military started pounding Jabaliya with airstrikes, leveling buildings to the ground. Israeli troops began advancing from the north and the east, getting closer every day.

I started looking for a home to rent in western Gaza City, where it was somewhat safer and where we could find some kind of shelter. On May 20, while returning from that search, my father called me in a panic to say a quadcopter was firing heavily at our home in the western Jabaliya camp. Our time was up. We had to flee. So we decided to spend the night at my brother’s burned down house in central Jabaliya.

We figured we would stay the night and leave the next morning, but that night we were plunged into the depths of hell.

Just two hours after arriving at my brother’s place, we heard someone outside shouting, “People of the neighborhood! The army is threatening to bomb the area! Evacuate immediately!” My legs began to tremble. Barely ten seconds later, the house next to our was bombed. It felt like the Day of Judgment had come, and my brother’s house would be next. I scrambled and grabbed some of my mother’s things, picked up my five-year-old niece, Deema, and ran down the stairs.

I found my mother—an elderly woman in her sixties—on the ground floor struggling to make her way through the rubble to escape. She could barely stand, and she couldn’t see in the pitch-black darkness. I held her hand, picked up the bags, and while still carrying Deema, we made our way outside. We walked, not knowing where we were going. We just walked blindly.

We couldn’t hear each other because of the shock. One person would say something and another would reply with something else. I was silent, unable to speak or think. We eventually made our way to my cousin’s house on Al-Jalaa Street in western Gaza City. I don’t know how we managed it. I don’t know how my mother was able to walk that far. I don’t know how Deema stayed asleep on my shoulder while I carried her and the bags.

The next morning, we managed to return home because the army tends to retreat slightly during the dayrun. We took advantage of that brief window to gather our things from our homes in west and central Jabaliya to leave for Deir al-Balah.

Two years before the war, my father had built the house we left in Jabaliya. He had just retired from teaching, and he poured his entire life savings into the multi-story home—with a 180-square meter apartment for each of his seven children. My older brother bought plots of land nearby for his children. We finally had some semblance of stability and a future. The genocide has crushed all of that.

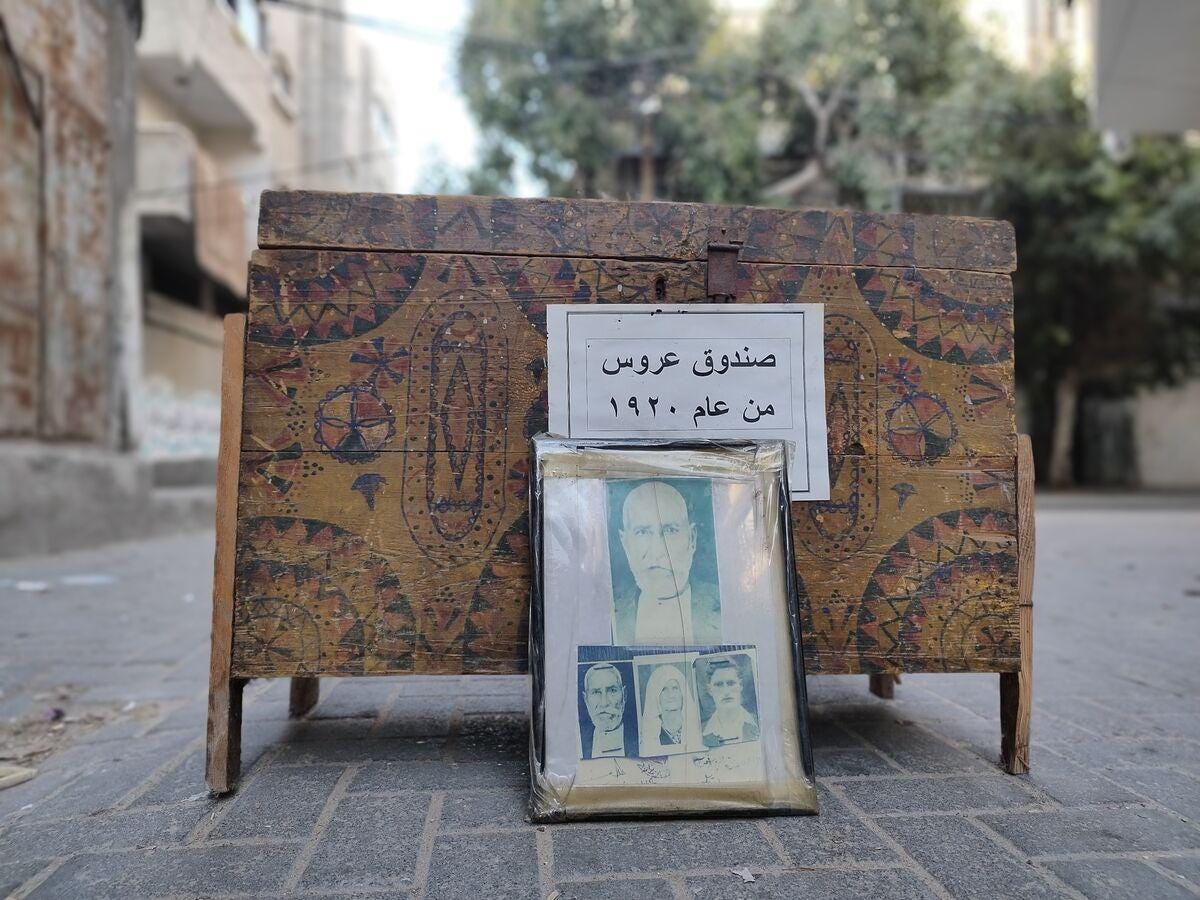

Every time Israel issued a displacement order, we were forced to leave it all behind. Yet we always managed to return. Since the start of this war, we only lived in our newly-built home for a total of two months combined, repeatedly moving back and forth in repeated displacements. We never got the chance to enjoy it or take in its beauty. Every time we received a new displacement order, my father said what would become a trademark phrase: “Where will we go? I feel like my soul is leaving my body. I feel a deep pain in my stomach.” We are living through what happened to my grandfather during the Nakba of 1948. At that time, he had lost 75 dunums (about 18.5 acres) of vineyards in the village of Barbara—some 17 kilometers (10.5 miles) northwest of Gaza City, near what is now the Israeli city of Ashkelon. My grandfather died in October 2024, while we were besieged in our home during the third invasion of Jabaliya. With little food or water, his health deteriorated after the start of the war, and it got markedly worse during each Israeli ground invasion of Jabaliya. On the evening of October 7, 2024, following a terrifyingly close air strike, he took his final breath. The Israeli army was just a few meters from our home. They had surrounded the cemetery, so we were forced to bury him in the grounds of our home. A few hours later, we escaped from the tanks and bulldozers and fled to Gaza City. The fourth Israeli invasion of Jabalia began on May 15—the 77th anniversary of the Nakba. The Nakba we are living through now is even more brutal and devastating than the one in 1948. Since then, Israel has made sure that every Palestinian generation has tasted the bitterness of the Nakba, so we can never rest or live peacefully. I have now become a refugee twice over: once from our historic village of Barbara, and now from Jabaliya, where subsequent generations of my family have been born and raised. Everything has been destroyed for us—my grandfather’s descendants—and we have become nothing. Ever since the first Nakba, our lives have been about building from nothing, and the Israeli army has set about destroying everything. They steal, and we lose. I try to overcome all of this, so I don’t lose my mind. I try to ignore the loss of our spacious home, where I once felt the utmost comfort, where my father had prepared for my future marriage. I try to believe that there’s a better future ahead of us. I try to look at the glass half-full—to think of life as a journey of movement and travel. But ever since I lived abroad in Spain in 2022, I’ve known that a person without a homeland is worth nothing. Leaving my home and my country felt like a lump in my throat. I used to feel inferior around my Spanish classmates, because they had the privilege of a homeland—something to protect them and offer them refuge. They didn’t face difficulties in traveling, and they could go anywhere in the world. They lived free of an occupation that controls everything in our lives down to the number of calories we can consume in a day. When the Israeli army forces us to move, they issue what they call “evacuation” orders. The Israeli army uses this to portray itself as an army that fights in accordance with international law—that distinguishes between civilians and combatants, that has no intention of harming children. This is far from the truth. The Israeli military has invaded and besieged many areas before issuing these so-called evacuation orders, as has happened in Rafah and Shujaiya. Israeli invasions force people to flee to so-called “safe zones” under heavy bombardment, making their way through checkpoints with nothing but the clothes on their backs, unable to carry even a day’s worth of food, any documents, or a blanket to cover themselves at night. Many of the leaflets the army drops on civilians contain terrifying threats that amount to psychological warfare. And then, they bomb the safe zones anyway. Anyone observing the conditions of the displaced people in Gaza can clearly see that the Israeli military doesn’t care about the fate of civilians at all. Israeli forces only tell them to flee—run!—and it doesn’t care where they will stay, what they will eat, or how they will live. Israel wants to force two million Palestinians in Gaza to cram into a tiny plot of land in the south—to live in tent camps with no infrastructure—where rivers of sewage run beneath their feet. Israel’s plan is to force people to leave their neighborhoods by labelling them “combat zones,” so they can destroy, bomb, and flatten everything to make them uninhabitable, even if the residents are ever able to return. All Israel wants is destruction and ruin, more land to seize, and eventually to establish settlements and pave the way for so-called “voluntary” migration, which many will be forced to accept after being broken by repeated displacement. Throughout this war, I never evacuated to the south, hoping to stay close to my home and return once the army retreated. I paid the price for that decision with injury and hunger. But now, for the first time, I am displaced in Deir al-Balah, staying at my aunt’s house. It’s the first time I have come south in some 15 years—since I visited my aunt when I was nine or ten years old. I don’t know how long my aunt will be able to host us, or where we’ll go when we leave. I tell myself we’re just here to visit my aunt after a long time—that I’m on a retreat or vacation somewhere else in the world—just to avoid dying from heartbreak over what we have left behind. The night we fled Jabaliya wasn’t the worst or most violent of the war. It was just another night from the depths of hell—like every night before it. But this time, we had no choice. We haven’t had a single peaceful night’s sleep since the beginning of the genocide. The deep, dark circles under my eyes are proof of that. Still, I refuse to accept this as normal. I haven’t gotten used to suffering. I just want to sleep one peaceful night before I die.A More Brutal and Devastating Nakba

From The Depths of Hell