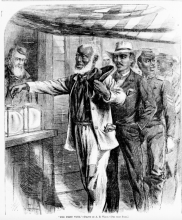

[Image from Harper’s Weekly, 1867]

While the news has been full of stories about how Trump-like Glenn Youngkin’s win in yesterday’s Virginia governor’s race spells disaster for Democrats going into 2022, the election news is not at all such a clear story.

The Virginia governor’s race almost always goes against whichever party is in the White House; indeed, journalist Eric Boehlert, who studies the press, noted that this pattern is so well established that in 2009, during President Barack Obama’s first term in office, when Democrats lost the races for governor of New Jersey and Virginia, the New York Times published only a single piece of analysis, saying “the defeats may or may not spell trouble for Democrats.” Boehlert noted that the New York Times has already posted at least 9 articles about Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe’s loss last night in Virginia.

And it was not altogether a bad night for the Democrats. In New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy won a tight race for reelection, making him the first Democrat to win reelection in that state in 44 years. Progressive Michelle Wu became the first woman and the first person of color to win the mayorship of Boston in 199 years; Democrat Eric Adams became New York City’s second Black mayor. Cities across the country elected Democrats of color.

If the meaning of the elections is hard to read, there are other stories to pay attention to that are much clearer.

The Democrats are trying to make a case that the government can work for ordinary Americans. They continue to negotiate over the Build Back Better Bill.

Meanwhile, the Republicans continue to focus on culture wars like the manufactured Critical Race Theory crisis, claiming that educators are destroying America. This is the formula Youngkin used in Virginia, and they appear to be running with it. Already, it is dangerous. Yesterday, at the National Conservatism Conference, J. D. Vance, who is running for the Senate from Ohio, quoted Richard Nixon’s statement that “The professors are the enemy.”

Attacks on professors are fodder for authoritarian attacks. They were standard for Cambodia’s Pol Pot, Italy’s Benito Mussolini, and the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin as they consolidated their power.

Nonetheless, Vance’s audience applauded his statement.

Republicans are using these cultural attacks to consolidate power in the states, 19 of which have passed 33 new laws to restrict the vote. In Florida, where Trump loyalist Roger Stone has threatened to challenge him, Governor Ron DeSantis has pledged to establish a statewide election police force to investigate election fraud, despite his earlier assurances that the 2020 elections were secure.

“I guarantee you this: The first person that gets caught, no one is going to want to do it again after that,” said DeSantis at a West Palm Beach event filled with supporters who cheered, “Let’s go, Brandon,” a euphemism for “F**k Joe Biden.”

The determination of Republican-dominated states to retake control of state elections and cut from the vote those they declare undesirable—usually people of color—echoes the arguments made by those determined to get rid of Black voters during Reconstruction.

Insisting that lazy Black men were voting for lawmakers who promised them roads, and hospitals, and jobs—things that would be paid for with tax dollars, levied on white men—former Confederates insisted that Black voting redistributed wealth from white people to Black Americans who would use the services the states provided. Black voting, then, amounted to socialism. Such a system was corrupt, former Confederates said, and good Americans must reclaim their country by “purifying” the vote. They were, they insisted, reformers, eager to “redeem” the South from corruption.

As white vigilantes tried to force Black men from the polls, Republicans in Congress gave to the federal government the power to protect the civil rights of Black Americans, as well as the right to vote, in states that would deprive them of these rights. Congress passed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution and sent them to the states for ratification. The Reconstruction Amendments explicitly declared that “Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” When white southerners continued to attack their Black neighbors, Congress did precisely that. In 1870, it established the Department of Justice to enable the federal government to enforce those rights in the states.

Quickly, southern whites changed their tune. They insisted they were discriminating against Black voters not on the grounds of race, but rather on the grounds of property ownership or education, criteria that northern native-born whites embraced as immigration from southern Europe increased in northern cities. After Mississippi wrote a constitution in 1890 that virtually eliminated Black voting, state legislatures across the country cut poor people, Black people, and people of color out of voting.

In 1898, white vigilantes in Wilmington, North Carolina, launched a coup d’état against the duly elected city government. The insurrectionists admitted that the government of Black men and poor whites had been fairly elected but, they said, such people should not be voters at all, because they would pass laws using tax dollars to help poor people in the community. White property owners were within their rights to refuse to be governed by such people, and they would never allow such a thing again.

In the process of taking over the government, they killed between 60 and 300 people, primarily African Americans.

In the 1890s, the federal government looked the other way as states suppressed Black voting, but World War II made lawmakers sit up and take notice of the silencing of American voices by state legislatures. Black and Brown Americans demanded a say in the democratic government they had defended from fascism, and in 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously decided the Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In response, white southerners launched what they called “massive resistance” against the enforcement of civil rights within the states.

Republican President Dwight Eisenhower backed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to enlist the federal government in the protection of voting rights in the states. After South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond (who had fathered a biracial daughter he kept secret) engaged in the longest filibuster in U.S. history to stop the bill, Congress passed it on a bipartisan basis.

Three years later, Congress gave federal judges more power to protect voting rights, and in 1965, Congress passed the national Voting Rights Act to make sure all Americans could vote. The vote in favor of the bill was bipartisan. Ten years later, Congress expanded that law to make sure ballots would be available in multiple languages.

The role of the federal government in protecting the right to vote has been a mainstay of our Constitution since 1870.

But today’s Republicans are standing on the same ground former Confederates did in the post–Civil War years, insisting that only states can decide how the people within those states live, and who gets to vote on those conditions.

Today, once again, Senate Republicans have filibustered a motion to begin debate on the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. That act would restore some of the provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights act the Supreme Court stripped away in their 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision. In 2006, when the Voting Rights Act came up for renewal, it passed the Senate unanimously. Today, the only Republican voting to advance the John Lewis bill was Alaska's Lisa Murkowski.

-